NPM Dependency Management Model

Dependency Resolution

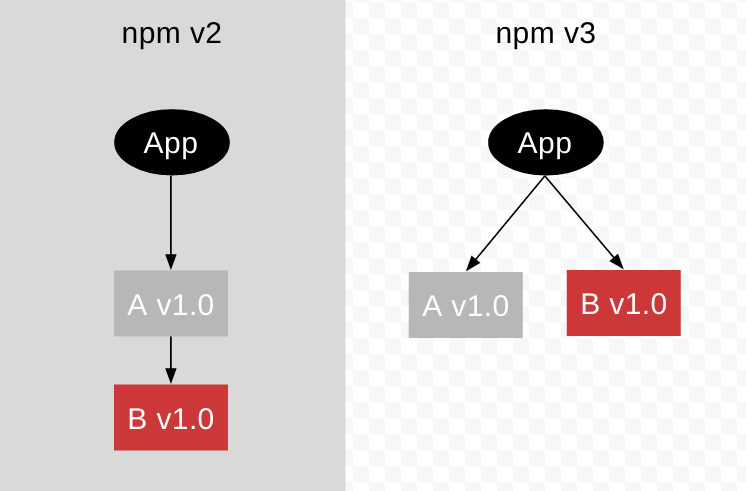

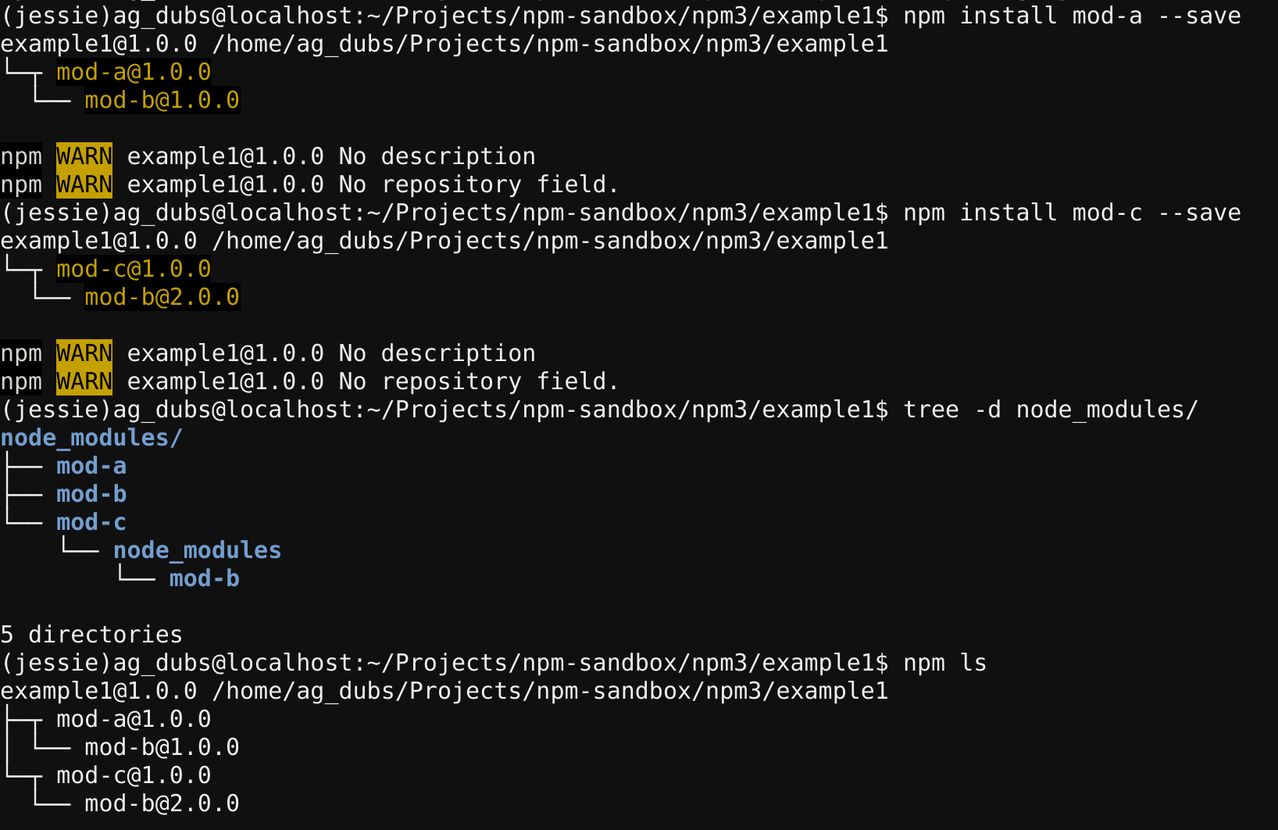

npm3 resolves dependencies differently than npm2.

While npm2 installs all dependencies in a nested way, npm3 tries to mitigate the deep trees and redundancy that such nesting causes. npm3 attempts this by installing some secondary dependencies (dependencies of dependencies) in a flat way, in the same directory as the primary dependency that requires it.

Imagine we have a module, A. A requires B.

Now, let’s create an application that requires module A.

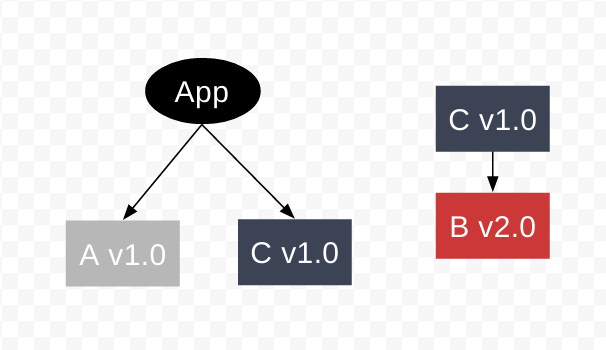

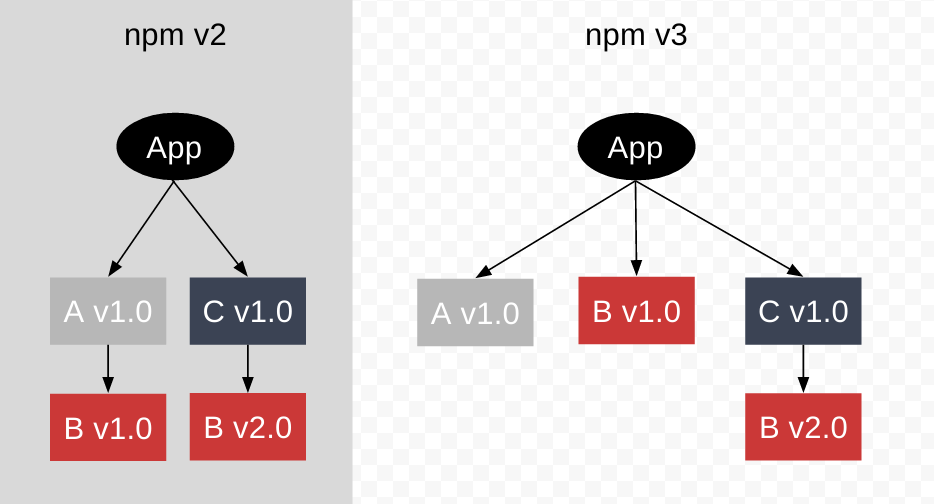

Now, let’s say we want to require another module, C. C requires B, but at another version than A.

However, since B v1.0 is already a top-level dep, we cannot install B v2.0 as a top level dependency. npm v3 handles this by defaulting to npm v2 behavior and nesting the new, different, module B version dependency under the module that requires it – in this case, module C.

Noted that you can list the dependencies and still see their relationships using npm ls.

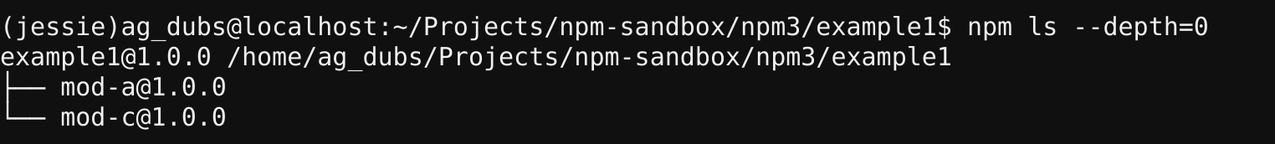

If you want to just see your primary dependencies, you can use:

1 | npm ls --depth=0 |

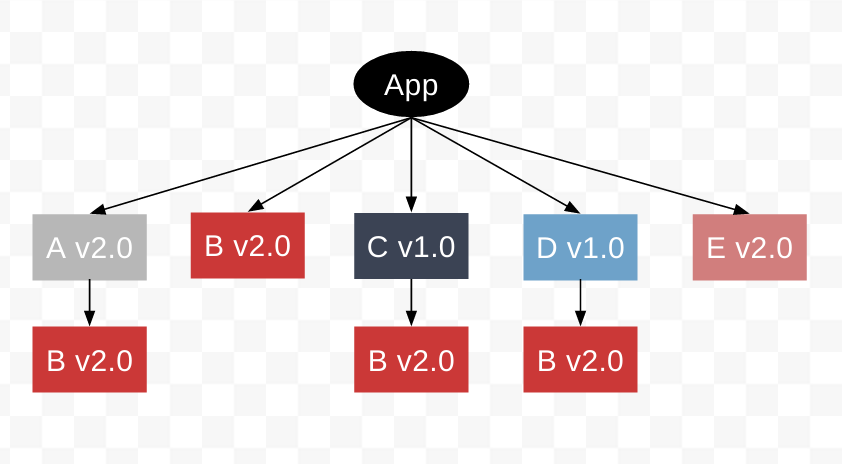

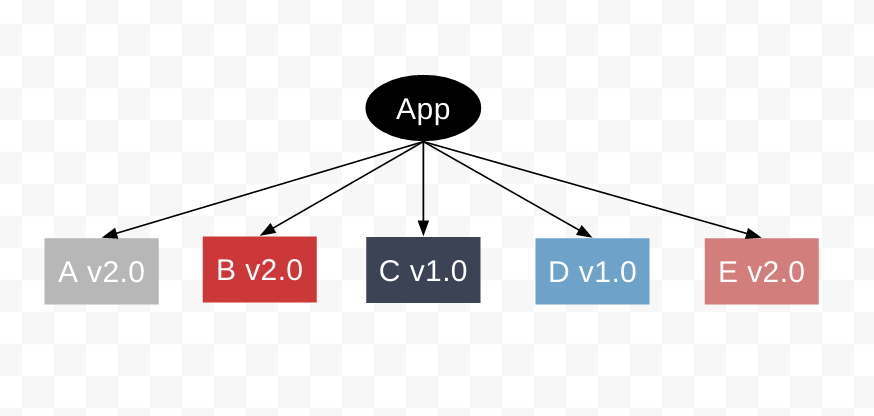

Duplication and Deduping

See Duplication and Deduping article for better illustration.

Use npm dedupe to get rid of duplication.

1 | npm dedupe |

Before dedupe

After dedupe

Comparision with Other Package Management Models

At a high level, npm is not too dissimilar from other package managers for programming languages: packages depend on other packages, and they express those dependencies with version ranges. npm happens to use the semver versioning scheme to express those ranges, but the way it performs version resolution is mostly immaterial; what matters is that packages can depend on ranges rather than specific versions of packages.

Npm installs a tree of dependencies. That is, every package installed gets its own set of dependencies rather than forcing every package to share the same canonical set of packages.

For example, consider two packages, foo and bar. Each of them have their own set of dependencies, which can be represented as a tree:

1 | foo |

Most package managers (including RubyGems/Bundler, pip, and Cabal) would simply barf here, reporting a version conflict. This is because, in most package management models, only one version of any particular package can be installed at a time.

In contrast, npm has a somewhat easier job: it’s totally okay with installing different versions of the same package because each package gets its own set of dependencies. In the aforementioned example, the resulting directory structure would look something like this:

1 | node_modules/ |

Pros

Extremely simple model but get pretty messy quickly.

Notably,the directory structure very closely mirrors the actual dependency tree. The above diagram is something of a simplification: in practice, each transitive dependency would have its own node_modules directory and so on, but the directory structure can get pretty messy pretty quickly.

Avoid “Dependency Hell”.

The npm model of package management is more complicated than that of other languages, but it provides a real advantage: implementation details are kept as implementation details. In other systems, it’s quite possible to find yourself in “dependency hell”, when you personally know that the version conflict reported by your package manager is not a real problem, but because the package system must pick a single canonical version, there’s no way to make progress without adjusting code in your dependencies. This is extremely frustrating.

Cons

Larger code size. Worse performance.

Given the potential for many, many copies of the same package, all with different versions. An increase in code size can often mean more than just a larger program—it can have a significant impact on performance. Larger programs just don’t fit into CPU caches as easily, and merely having to page a program in and out can significantly slow things down. That’s mostly just a tradeoff, though, since you’re sacrificing performance, not program correctness.

Dependency isolation can affect cross-package communication.

See this Dependency isolation and values that pass package boundaries section for detailed illustration.

An failure example: Dialog will break if two version of botbuilder-dialog package exists

PeerDependency

PeerDependency: Rather than getting its own copy of a peer dependency, a package expects that dependency to be provided by its dependent.

The peerDependencies requires npm v7. For npm >= 3 and npm <= 6, peerDependencies can be declared but will not be automatically checked and installed.

That is to say, to leverage the peerDependencies feature, we will need to migrate to npm v7 as well as requiring user to update to npm v7.

Node:

- LTS: 14.16.0 (includes npm 6.14.11)

- Current: 15.10.0 (includes npm 7.5.3)

Though node use npm v7 as the current version, the majority will be using npm v6 in 2021. Consider the population, asking user to update to npm v7 adds a new pre-requisite.